The ‘Time to Value’ Equation

With inflation, rising interest rates, diminishing access to capital and fear of a recession, leaders have good reason to invest cautiously. They may even be justified in postponing some of their investments and reducing costs to maintain sound financial management of the organization.

Through all this turbulence, investments in IT—particularly the modernization of management applications, data science and cybersecurity—should continue to grow at a rate of five per cent per year by 2025, according to Gartner. Despite this, IT managers have never faced so much pressure. The message from the top is clear: Yes, we are investing more, but show me the money!

For IT managers in the midst of planning a budget for 2023-24, the notion of “time to value”—the time necessary to feel the benefits of an investment—becomes an important consideration. But what exactly is value? How do we define it in concrete terms? Is the definition the same for all stakeholders involved? These underlying questions are equally important.

The notion of value

In business, when we think of value, we inevitably think of financial returns. This form of value is typically calculated using the return on investment (ROI). This model considers net profits divided by the initial investment. It is tangible, concrete and direct, and above all, aligned with the performance expectations of a specific target: the organization’s shareholders.

But in such a complex and turbulent world where the expectations of stakeholders—beyond shareholders—are often contradictory, even conflicting, does this model still hold? Some experts say no: Managers using only this model will miss investment opportunities that could bring critical value to the sustainability of the organization. It could also create discontent among certain stakeholders and damage the reputation of the organization.

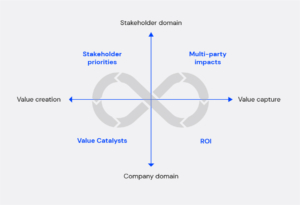

The notion of value should be considered on four axes, of which the benefit to shareholders is simply one of those axes. For the other three axes, value is not just monetary—at least, not immediately.

In this model, the notion of value (the X axis) is divided into two: it can be created and it can be captured. It can contribute either to the company and its shareholders (the Y axis) or to all stakeholders—the company and its shareholders, as well as employees and society at large. In other words, certain investments could be used to create value that would not directly benefit the shareholders in the short term.

The second relevant element of the model is that it integrates the notion of time. For an organization that doesn’t have an unlimited budget to invest, this illustrates that at a specific moment in time each dial is in conflict with one another. Indeed, a single investment cannot both create value and capture it in the form of ROI for the shareholder. However, it illustrates the notion of a boomerang: seen over time, an investment in value creation will eventually generate a return.

Here are some examples of value that can be created through different types of investments:

The dials make it possible to choose a definition of value for a given investment, and the aspect of temporality makes it possible to trace a “path” from creation to the capture of value by the shareholder.

Time to value: A concrete example

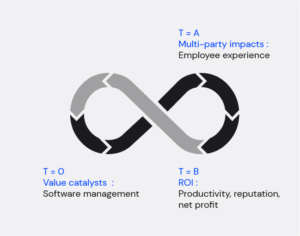

In the context of a labour shortage, postponing investments in IT (a value catalyst) can lead to a reduction in employee retention and hiring challenges (multi-party impacts). This would not immediately be calculated in an ROI. In fact, not investing in an IT project will generate a higher operating margin, directly increasing the net profits of the organization and, therefore, the shareholder. However, the impact will be felt in the following years.

For a management team, the goals of improving the employee experience, rolling out effective management software and generating higher net profits—all over the course of the following year—are not aligned. They could even be conflicting. However, if the management team reviews its value calculation model and integrates the notion of “time to value” into the discussion, there’s a way to align these goals. Indeed, better management software this year could increase yield for the following year.

For the IT manager who must defend his or her investment, especially during a period of economic turbulence, this model can be used to demonstrate time to value. For example, a values catalyst could lead to a better employee experience over the current financial period, which will be captured in ROI in the following period. There are several studies and reports that can help you build a compelling case and, above all, estimate the time needed to go from creation to capture of value.

ROI is no longer the sole measure of the value of an investment. It’s imperative that leaders update this model to be more encompassing and, above all, offer a notion of temporality. It’s also essential that IT managers demonstrate that over a longer period their investments are aligned with both the expectations of the stakeholders and the shareholders.

This article is part of a series of articles on the major questions facing CIOs. To receive our next articles on the subject or to read the articles already on file, go to logient.com. Subscribe to our newsletter and learn how to face the complex business challenges of today and tomorrow—and stay tuned via our LinkedIn and Facebook accounts.

Source: Salam, R & Al. (2022), The Gartner Enterprise Value Equation: It’s Time to Rethink Outdated Enterprise Value Formulas. Gartner, ID G00770206.